THE BRIDE BACK IN GALVESTON

Pittsburgh Landing, Tennessee — April 7, 1862

Dispatch from Lieutenant Micah Boone

My dearest Nelly,

I hope this letter finds you in good health. How is Galveston faring during the war? Has my father been able to keep up with the farm? We receive little news from home, and I hope when you write me back you can tell me of yourself, our families, and our town. I miss them all, and I can hardly wait to return and finally be wed to you, my dear. The thought weighs upon my mind more than I ever imagined it would, darling.

Are you still playing your piano and giving lessons? I so miss hearing you play. When we march, I sometimes find peace thinking of your beautiful rendition of Aura Lee. The song runs through my head again and again, and I almost believe Fosdick and Poulton must have known someone like you when they wrote it.

I’m writing from the little Shiloh church in Tennessee, not far from the Tennessee River. Though I am bone-tired after yesterday’s fighting, I cannot sleep. The men elected me lieutenant, darling, an honor I pray I will be worthy of.

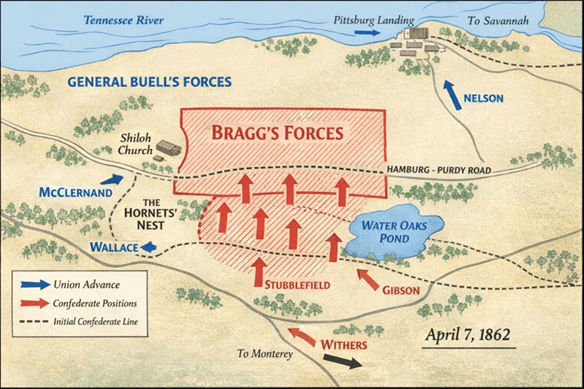

Word is that General Grant himself is here at Shiloh, commanding the Yanks — the place must mean much to them. They are after the railroad hub at Corinth, Mississippi. General Albert Sidney Johnston commanded our army, but he fell yesterday afternoon. He was struck behind the knee and refused to leave the field and bled to death. He has been replaced by General P. G. T. Beauregard. Our corps commander is General Braxton Bragg.

Under General Bragg, we were placed in the center, around a place they call the Hornets’ Nest, south of the Hamburg–Purdy Road. They say we have tens of thousands of men here. I can scarcely believe the number.

Yesterday was miserable. The ground is soaked and the men grumble about sleeping on the wet ground, but the church cannot hold us all. I have a pew for a bed tonight. The woods are thick with oak and underbrush, and the gunfire sounds nearer than it truly is, keeping the men on edge. Smoke hangs low and makes it hard to see. We would fire, step back, fire again — sometimes advancing a few paces, other times falling back. None of us expected there would be so many Yanks.

There are dead everywhere, blue and gray alike, Nelly. We do not yet know the number, but it is terrible. In only a few hours we are to go out again.

If you did not receive my last letter, I wrote that Abner died on our way north, when a frightened horse fell on him. This fighting is nothing like we imagined when we joined. We thought we would defend Texas; instead I am here in Tennessee, and Abner lies dead.

Bragg is brave, Nelly, but he drives men too hard and punishes often. He pushes us forward no matter the cost, and many despise him for it. They say that if he did not know President Davis, he would have been relieved of duty long ago. Keep this to yourself, please.

Gunfire has begun from the north, and they are calling for us. It falls to me to rouse the men, though most have scarcely eaten and none have slept. I will write again as soon as I am able and tell you where we are and how we fare.

Your loving,

Micah

The Evening of April 8, 1862

Letter from Lieutenant Caleb Uriah Hood to his wife, Sarah

Dearest Sarah,

I trust you and the children are faring as well as can be expected. I miss you. Give the children my love. I have not yet heard word about the farm — perhaps your letter has not reached me. I hope Joseph Applewhite continues to be a good hand. See that Caleb Jr. works alongside him and learns all he can. At fifteen he ought to carry a man’s share. If he keeps to the plow, perhaps the war will pass him by.

Our unit is encamped a short distance from the ground where we fought these last two days. The men are worn out and have fallen asleep wherever they could find a patch of dry earth. I have been detailed to the sorrowful duty of marking the fallen and making what record can be made. It is hard work, yet I thank the Lord that I have been spared to write you tonight. Thus far we count more than fifteen hundred Confederate dead, and many hundreds wounded besides.

The woods are torn and splintered. Powder smoke still hangs in places. I will not burden you with details, except to say many good men are gone. Others will return home maimed. When our duty here is finished, we expect to march again to meet up with General Bragg. If you do not hear from me for some time, do not be alarmed — it may only mean we are on the move.

This afternoon, while walking the line with two sergeants, we found several officers where the fire had been worst. Among them lay Lieutenant Micah Boone, the young Texan from near Galveston whom I once mentioned. He had only lately been elected by his men and spoke often of a girl at home, a farm, and a piano in a sunny parlor. He seemed a good young man.

He was lying near the edge of the woods, quite still, as if asleep, but he had died. In the breast pocket of his coat I found the letter I sent with my own. He must have written it the night before and died before he had the chance to send it. I could not bring myself to leave it there.

Please read Micah’s letter within this one. I don’t know whether I ought to ask you to send it on to the girl who waits for him. There is a cruelty in letting her read such hopeful words, knowing the hand that wrote them now rests in Tennessee soil. Yet there may be a greater cruelty in letting his last thoughts die with him.

Sarah, you have more sense than I, and a softer heart besides. Tell me what you think: should we forward the letter to Miss Nelly Anderson, or hold it until some better time? I fear that whatever I decide, grief will find her just the same. This war makes us stewards not only of the dead, but of the words they leave behind.

Know that I am safe for the present, and that I carry you in my thoughts. I will write again when I am able.

Your loving husband,

Caleb

Authors Note – This story is historical fiction, inspired by the Battle of Shiloh and real wartime letters